Opening Eyes to See Clearly

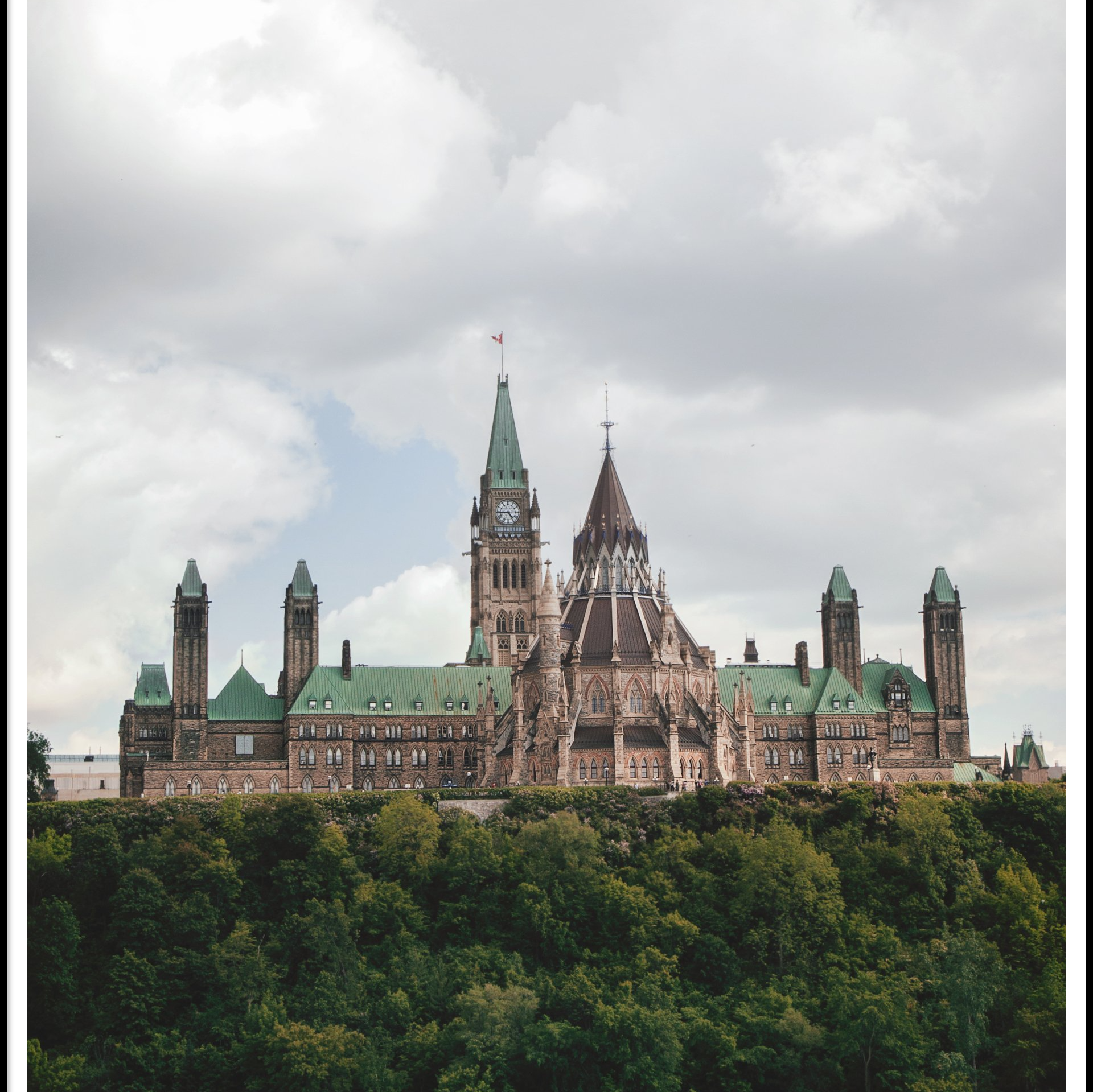

The Parliamentary Library - a Treasury of Information to Be Learned

1950s

In 1955, four years after emigrating from The Netherlands to live in the USA, I crossed the border at the Peace Arch into Canada with my parents and sibs. We settled in Vancouver at 49th Avenue and Fraser Street – the start of a lifetime as Dutch Canadian Christians. As an 11-year-old, I just assumed that we, like the others in our neighbourhood, were sometime immigrant settlers. There were people from India, China, Germany, Italy, Ukraine with varying cultural traditions and religions.

At that stage I didn't notice in that urban setting any “Indian” population, who were actually close at hand at the Musqueam Reserve on the University Endowment lands, on the shore in North Vancouver, or south of us at Tsawwassen. My only reference to “Indians” was when chums and I played at being cowboys and indians. Our family was aware of the downtown east side as skid row where poor, addicted people – of varied backgrounds – survived or not, but not yet as a place where many urban Indigenous folk subsisted.

1960s

By the mid-1960s, I’d graduated from Gladstone High School and got a B.A. degree in history and German from UBC. In all that learning, there was hardly a thought about how Turtle Island became Canada and even less about the Indian Act’s brutal impact on Indigenous peoples. In 1965, I moved to Toronto to study theology at Emmanuel College and spent two summers as a student minister in Manitoba. In Emmanuel as in UBC, I was a history buff; but, hard to credit, I spent no time learning about the crucial relationship between colonial settler culture and Indigenous people – not even about Canadian church history! I hadn’t learned to explore our own Church’s role in contributing to the presumed superiority of Euro-based settler culture.

In May of either 1966 or 1967 while serving on student “mission fields” in Ste. Rose du Lac and Whiteshell Provincial Park, I attended the Annual Meeting of the United Church’s Manitoba Conference. There I encountered, memorably, real “Indians” – Indigenous persons from northern reserves like Norway House or Cross Lake hovering at the edges of the gathering, I remember no effort – either personally or programmatically – to bring us together for conversation or understanding. It still haunts me.

1970s

In the 1970s, as an ordained minister in a downtown Toronto church, I remember well the heroic efforts of one leading woman with others regularly gathering up clothes and equipment, like sewing machines, to help reserve “Indians”. These were acts of generously motivated charity to address immediate conditions, but with little effort to grapple with causes Indigenous social and economic deprivation.

It was also the time I became aware of “scooped” Indigenous children adopted by settler families, doubtless motivated by the desire to “better the lives of Indigenous children.” We didn’t ask much about the why and how these Indigenous children needed such intervention, whether they would lose their family heritage, or why it was that “Indians” were living in poverty when most of us Euro-Canadians weren’t.

1980s

In the 1980s, there was in me and our little family as well as in the church as a whole, a turning of tides. My spouse, Glenys Huws, assumed several staff roles in the United Church’s Indigenous initiatives, bringing our family into close relationship with numerous Indigenous leaders – like Gladys Taylor, Murray Whetung, John Williams, Dolly Lansdowne, Peggy & Neil Monague, Bob Patton, and others.

The Church launched consultations for Indigenous church people to gather nationally to tell their life stories under the colonial settler-dominated church and nation. In emotionally-laden talking circles, Indigenous people shared stories of their experience of marginalization, racial injustice, imposed dependency, and poverty. They spoke of the political domination and presumed church superiority in matters spiritual; but they also shared their courage, generosity, determination, and hope.

The settler United Church was listening: on advice of Indigenous leaders, it created theological schools by and for Indigenous people to learn and lead their faith communities; organized church life for greater autonomy of Indigenous faith communities; fostered links and gatherings that enabled Indigenous folk to make their case and challenge racist ways.

In 1985, a courageous representative woman, Alberta Billy, called for the Church to apologize for the way it had related to Indigenous peoples in its midst. In August 1986, the General Council meeting in Sudbury acknowledged the Church’s sins of the past in an Apology to Indigenous peoples of the United Church. (A further apology to students of residential schools and their families was offered in 1998. https://united-church.ca/sites/default/files/apologies-response-crest.pdf)

Remarkably, there was still no recognition of the historical political context which had led to the theft of Indigenous lands by Canada’s government to grant possession to waves of new settlers and licences to corporate interests plundering the lands. I and the Church still hadn’t fully understood, acknowledged, or condemned as a crime against humanity the Canadian “apartheid” system - the Indian Act - proclaimed as law by the Crown in 1876, even as we were all clear and vocal about the evils of the system in South Africa. Even the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples report generated but small waves.

1990s

In the 1990s, the entire Indigenous Colonial-Settler relationship came under intense scrutiny when the horror of Residential Schools became general knowledge. Early stories of abuse, deprivation, violence, sexual assaults cast huge shadows on the story of these government initiated and Christian-church-run compulsory institutions. Ostensibly, they were designed for the educational benefit of Indigenous children, but in reality, the policy which created them aimed at deleting the “indian” out of children and assimilating them into European and Christian modes of being – a genocidal system.

2000s

These “schools” modelled white and Chrisian superiority, along with merciless, abusive power over Indigenous children and families enforced by the Indian agents and the RCMP. The last school was finally closed in 1996. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission report of 2015 recorded for the nation and the world the system’s devastating impact. It called for 94 “Calls to Action”.

Yet another investigation focused on murdered and missing Indigenous women and girl and produced a report with recommendations in June 2019. Its finding were documented in Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/timeline/).

There are no end of reports, recommendations, and resources to study and address the problematics of the Colonial Settler and Indigenous relationship. Lack of information and data is not the failure. But what I can now admit (and perhaps others too) is that it really escaped my notice that there was an unaddressed problem at the heart of this substantially malignant relationship between Settler and Indigenous peoples.

The fact was that the acquisition of the Turtle Island lands, resources, and waters and the unfounded pretensions of Crown sovereignty over Indigenous Peoples underlay most problems and had no basis either in conquest or in law.

This reality was all based on a phony Papal claim to speak on behalf of the Divine, declaring that any lands “discovered” and found to be “vacant lands” (terrae nullius) could be claimed by explorers for the European sovereigns who had commissioned them, e.g. Cartier for France and Cabot for England, etc. (see my blog posts at https://www.minister.ca/beyond-the-doctrine-of-discovery; https://www.minister.ca/towards-a-new-way-for-canada )

2020s

I’m embarrassed to admit that I only really stared this startlingly obvious presumptuous fact in the eye in March last year when I watched the “Doctrine of Discovery” film produced by the Anglican Church of Canada. With the Covid 19 social shut-down, I had time to explore the sordid history, increasingly from the vantage point of the marginalized and oppressed Indigenous Peoples.

There has been much to learn and much reality to deplore. But I have benefitted much from the reams of factual information, knowledge, and wisdom which Indigenous researchers and scholars have been generating to help settler folk, like me. I discovered how much we settlers have gained from the theft of Indigenous lands, and how steadfastly Indigenous peoples have sought truth to be revealed and justice to be served. For more than a century and a half, the governments of Canada have been parceling out properties and assets on land and sea to settlers and corporations, or retaining land as “Crown” properties at the expense of Indigenous people and largely without their consent.

The discovery of the many children’s bodies buried – initially in Kamloops and since then in so many other Residential School yards – has touched Canadian hearts, opened minds, and awakened demands for justice. Justice – yes for the children buried, but also for the succeeding generations injured by the whole campaign to erase “Indian” out of Indigenous lives; justice in recognizing Indigenous claims of land and resources; and justice to transform the settler / Indigenous relationship.

What I have really learned all too recently is that the costly, wearying, malignant, and unjust relationship will continue unless the federal and provincial governments acknowledge the fatally flawed foundations of Canadian sovereignty.

Governments must acknowledge the urgent need to invite a representative assembly of Indigenous leaders together to negotiate a new way of being together on the Turtle Island lands. Governments must relinquish manipulative policies that require costly litigation rather than authentic negotiation. Governments must acknowledge the legal right of Indigenous peoples to consent or not to proposals affecting their traditional territories and resource rights (see UNDRIP articles 25 to 32: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf ).

Governments and all Canadians must acknowledge that Indigenous Peoples have sovereign rights that have never been extinguished and must be honoured. (See the Yellowhead Institute's two informative reports: "Land Back" and "Cash Back" at https://yellowheadinstitute.org.)

I have also learned that by my ignorance and lack of attention to the systems burdening Indigenous Peoples, I am part of the problem and have contributed to a status quo which benefited me and harmed Indigenous Peoples.

I apologize for that apathy and hope that my activism toward a more just relationship is neither simply another Indigenous-washing approach nor an empty, temporary noise. Rather. I commit to a shared informed activism that leads to more just relationships, greater partnership, and a transformed vision of Canada, where my relations with Indigenous people are based on respect and justice, on generosity and sharing, on appreciation of diversity and on other-affirming humility.

The Golden Rule and the Great Commandment which I - as Christian - profess have far-reaching implications!

More to come……